Gerry Hassan has expanded, generously to say the least, on my earlier post about the place of the Scottish national team in the minds of Scots. I’m going to begin my response by considering some of Gerry’s points. But his fasinating post has attracted exactly the kind of in-depth, thoughtful, informed comments that I’ve found more common in discussions of Scottish football by Scots than in equivalent discussions of English football by the English. That isn’t an anti-English comment – both countries suffer by comparison with the Netherlands – but I’m not sure how aware Scotland is of the presence within its borders of various manifestations of quality to do with the national sport and feel this particular manifestation is worth pointing out.

Anti-Englishness

Gerry says of anti-Englishness:

One of the worrying trends is that you can see such a phenomenon across society: in the support for anyone playing the English at football, in the slow rise of a bigoted anti-Englishness, and related to it a kind of romantic, sentimental national feeling (I wouldn’t credit it with the intelligence of a nationalism) which mixes ‘Braveheart’ with ‘Whiskey Galore’.

I’ve not been in Scotland long enough to comment on longer-term trends. But I have had experience of anti-Englishness in Scotland: the experience of not experiencing it. “Hating the English” is one of those things that a small subsection of society get up to, and because (a) they themselves believe it and (b) they think themselves the salt of the earth, they think everyone feels the same way. Everyone who’s really Scottish, of course. Most Scots don’t seem to agree, and regard hatred of the English as (1) insulting to their English friends, girlfriends, wives, relatives (2) racist (3) dim.

It’s weather talk, code, not real. I’ve been warned several times about certain people that they’ll hate me because of my origins (I don’t consider myself English – I’m a Londoner, and other Londoners will catch something of what I mean even if they don’t feel that way themselves). Every time, without exception, the person to whom these dark mutterings referred turned out to be more inclined to open a second or third bottle with me and talk the sun back into the sky. I’ve come to read “I hate the English” as “I love Scotland, and I’m proud of it, for all its faults and shortcomings: I want to be warp and woof of this place of places.” Every time I drive up the A9 into Perthshire and beyond – every time a stranger takes me into conversation on some Glasgow suburban station – every time I smell the breweries on the Edinburgh air – so do I, but then I feel Gloucester Road calling me and pull away from the thought.

Football as an anchor point

Gerry has a three-point strategy intended to place football in a healthier place in Scottish culture:

First, to put football in its proper context in an age which we are constantly told by IT gurus and new economy geeks is constantly filled with choice and diversity, and yet which in many respects has become narrower and more conformist. Is football used by (mostly) men as an anchor point in a culture of chaos and confusion, and why do we not want to talk about that?

I can think of one important way in which the age has become narrower and more conformist, namely the prohibition of recreational drugs in the late 1960s. And one unimportant way: the rise of management-speak (although I think all that’s done is replace earlier forms of the same thing). I’m not sure, either, that we’re being told that the age is filled with choice and diversity: some commentators would like more, and others see diversity as a general good that gives breathing space to immigrants, ethnic minorities and social minorities (and that’s my view too). But Gerry’s core point is the use by men of football as an anchor point and maladaptive displacement activity, and here I have to plead guilty.

I don’t agree that we live in a culture of chaos and confusion – compared with the 1870s, or 1919-23, or 1946-50, or 1979-81, the UK is a laughing paradise. And compared with the period of industrialization and urbanization of the nineteenth century, life has been stable and unchanging to an unprecedented degree since World War Two. Compared to the lives my grandparents lived, my 40-odd years have dodged every imaginable bullet. So what about the use of football as an anchor point?

The bullets I didn’t dodge – parental breakups plural, having my skull fractured in a mugging outside my house, unemployment, business failure etc. – have left me at times, yes, taking comfort in something stable and ongoing and distracting. After my mugging, I determined not to let my attackers or the experience beat me, just as I’d refused them my wallet until I realised my injuries were becoming serious. I kept my same haunts, my same walk home. It was about as frightening as I could endure, but for the first week or so I managed. Then I met the same gang again, and they, recognising me, gave chase. I ran into a nearby shop, and, as I was no longer alone, they left me there. The shopkeeper had a television on behind his counter, and there was a match on. Memory says it was Leeds v Rangers in the European Cup. Memory also says that I watched it with the shopkeeper, and found that bit by bit the sheer ordinariness of it all and the shared company helped me pull myself together enough to get home. I moved away shortly afterwards.

Likewise, during the early credit crunch when the business I’d spent a decade building began its rapid break-up, I don’t think I missed a single Match of the Day, and my 3-DVD set of old MOTD editions – an at-hand reminder of earlier, relatively safer days – saw heavy use. “Look at his face!.. Just look at his face!…” that would be Franny Lee’s, and, next morning, my own, longer, dead-eyed one in the shaving mirror.

I’d regard the use of football as a comfort and distraction from problems as an entirely positive thing. The fact is, it only lasts a short while. In hard times, the information comes at night, as Martin Amis says, and I’ve known it turn up during daylight hours too,to check if you’re busy. That’s why I don’t believe that men are using football talk to dodge realities (I’m reading Gerry’s point as meaning “political realities”) and why I don’t believe men are talking about football instead of what they ought to be talking about. I agree that awareness and consciousness trump their opposites, but I don’t get to define those terms for other people, and in troubled times, you are all too aware, aware of things that are all too close, for any sustained conceptual analysis or bigger picture.

As fans of Simon Kuper know, in unfree political societies, football talk elides into political code and political representation naturally and automatically. The flipside is also true: where free political discussion, campaigning and voting are available, politics and football separate off, unless they are kept together by sectarianism on the one hand or by political self-consciousness (nostalgia for crowds of cloth caps being run together with Liverpudlian socialism, for instance, or the Guardian’s ethical World Cup).

Which leads me to want men to keep the football talk: if the UK really does abandon the free political culture of the later twentieth century – and I think the illiberal urge is at its zenith now, about to go out of fashion and into decline – then they’ll need it. It’ll cover a multitude of tiny, hard-won illicit freedoms, as it did in Nazi Austria and the post-War Communist bloc and as it does today in China.

Know Your History

Gerry’s second point:

Secondly, the Scots need to address some serious issues about their culture and society. Knowing a bit more history: both real and on the football field would be a good start.

Yes, absolutely. Scottish history is avowedly not a story of innocent kite-flyers repeatedly, pointlessly, intruded upon by rosbifs; Scotland is not under occupation nor has it been oppressed. I refer the reader to Alex Massie’s recent exchange with his readers over the issue of the Council Tax – it ends with his nationalist opponent resorting to the surreal claim that St Andrews isn’t really part of Scotland. Whether or not you support independence, it’s hard not to admire the efforts of the bulk of the SNP to create a vision of the country’s future that is open, forward-looking – a vision antagonistic to the paranoia and parochialism of the kind of nationalism that shapes the Glasgow omnibus version of even recent Scottish history.

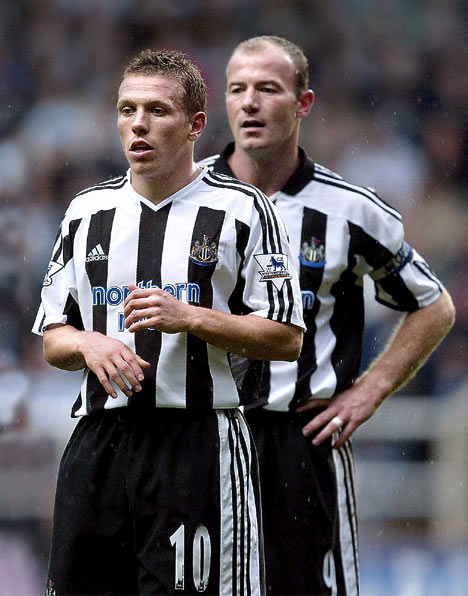

I agree with Gerry that there are, if you want them, credible ways of addressing Scottish history that nourish rather than tear down, encourage rather than depress, unite rather than divide: the story of the national football team is one of those. (I think I can speak for both Gerry and myself in deploring, ultimately, the idea that the discipline of history has to be “for” anything, let alone this). I’m old enough, for example, to remember the excitement around the 1978 Scotland team of Dalglish and co. – excitement, that is, in the Home Counties of England, and to remember the sheer force and pleasure of the reflected glory felt in England as Scotland beat the team of the tournament with the goal of the tournament. Humiliated? Who was humiliated? England wasn’t even there: they hadn’t come close to qualifying.

What to do about the Old Firm?

Gerry’s third point:

Finally, it would be great to do something about our football, the sad awfulness that is the Scottish Premier League and the nature of ‘the Old Firm’. Maybe getting them to commit to the Scots domestic game for the next ten years and engage in a root and branch transformation, which would involve Celtic and Rangers seeing their successes as interlinked with the success of Hearts, Hibs, Aberdeen and Dundee United.

I waver over the “Old Firm.” As a small boy who didn’t know anything about a row between any Catholics and Protestants, I started supporting Celtic because I liked their name, and was delighted, once I could read properly, to find out that they’d once won the European Cup and were actually quite good. Lucky, happy accidents: I picked up my English team by turning on the FA Cup Final by mistake in 1976 and, being a good little Brit, cheering on the losing team..

Holland has the same “problem”, for instance, of domination by a pair of big clubs, yet still produces stunning footballers. My favourite foreign team of recent years is Ajax 1995. And, given enough determination, other Scottish clubs can compete: Hibs are coming up fast on the Old Firm, and not as a one-off one-season blue streak. Hibs have worked hard to build infrastructure, and have a period ahead of them now when Celtic and Rangers will be hobbled financially. There’ll be at least one league title at Easter Road to show for it.

Root-and-branch transformation might well happen, too: the blogs are shouting for it, the former First Minister is putting a plan together for it, the new Scottish manager wants to be involved in it, there are no illusions in the media about skimping on it, and there are men and women – especially in Ayr and in the unsung Highlands – who aren’t waiting for anyone else and are getting on with it themselves. In Edinburgh, there isn’t just the new Hibs training complex: there’s also Spartans, one of the most inspiring non-league clubs in the UK.

I’m pessimistic, for now, about the national side. As I said in my initial post, I think the job is beyond the reach of anyone at the moment. Football, I think, is where the English go to be stupid: where a literate and intelligent country lets its hair down. Sir Trevor Brooking is a lonely figure down there sometimes. The Scottish value intelligence and its expression as a positive thing – just read the comments on Gary’s post – and are able and willing to put proper minds to work on the national game. That won’t, however, stop the mass media going all Greater Serbia over the national team, but, then, perhaps those reporters don’t, in the end, know anything about the game.

Sportscene is filmed on a depressing, recession-blue set inside what appears to be an abandoned refrigerated warehouse. The presenters wear the expressions of doomed men. To the right of the screen flicker latest scores from little clubs playing in cold places at the end of single-carriageway trunk roads. Two retired players with earthworm complexions discuss Motherwell and Falkirk. What they have to say is articulate, intelligent and interesting. But in context, it feels like something is coming to an end here.

I do think something is coming to an end. It goes for the whole of Britain that, when the last of the comfortable predictions has died out and all is dark and wet and frightened quiet, good things are beginning. So it is, I think, for Scottish football. It’ll take many years for it to reach the national side, for reasons I’ve discussed before. But the worst is over, before we know it or are aware of it. It feels like 1980 in Scottish football: all unemployment queues, dodgy auction surplus shops in the High Street and no one to vote for. There are people in the jungles of Scotland who fight on unaware that that early ’80s recession has been over for thirty years. The football one’s over too, for all that it doesn’t yet show. When it does, it’ll become clear that the Scots pulled themselves out of it, on their own and on their own resources, and it’ll be a point of pride in the end. But even in my own, sunny version of Scottish football history, it’s been a low and bitter period for all kinds of reasons.

Getting back to the good days is like leaving a capital city by train. You do it through tunnels, and each time you think you’re out and free and can stop swallowing to unpop your ears, you’re back in the dark again. By the time you hit the suburbs, you’ve lapsed into a sullen acceptance of bad artificial light and your fatty, middle-aged reflection in the window and the filthy wire-strewn brick beyond it. Forty minutes later, everything’s been fields and sunshine and rich oaks and dude ranches and good times out there for as long as you can remember.